When appropriating history becomes inconvenient: Decoding BJP’s Bankim Chandra problem

India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has a talent for historical revisionism. The party’s latest project involves transforming Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, a 19th-century Bengali novelist, into a Hindu nationalist icon. The timing is strategic. West Bengal holds assembly elections in 2026. The BJP needs Bengali votes. What better way than to claim ownership of Bengal’s literary giants?

There is only one problem. Bankim Chandra’s actual writings are rather at odds with everything the BJP stands for.

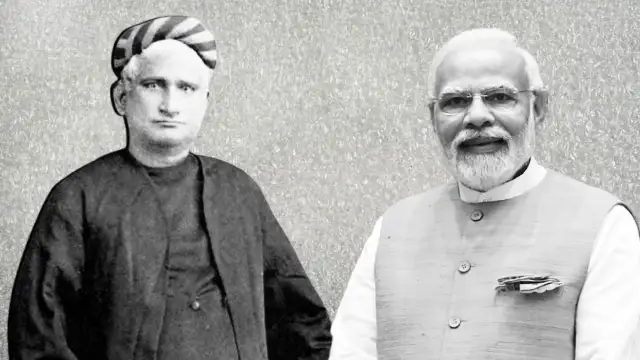

The issue came to a head in December 2025, when India’s Parliament held a ten-hour debate marking 150 years of “Vande Mataram” (“I bow to thee, Mother”), a patriotic song from Bankim Chandra’s novel Anandamath. Prime Minister Narendra Modi addressed Bankim Chandra as “Bankim Da”—a form of address that made Bengali speakers wince. Union Culture Minister Gajendra Singh Shekhawat went further, mangling the name entirely to “Bankim Das Chattopadhyay”. One imagines the ghost of Bankim Chandra quietly despairing.

These errors are not mere ignorance. They reveal a deeper problem in the country— the BJP is trying to weaponise a writer it has not bothered to read properly.

Inconvenient socialist

Consider Bankim Chandra’s five essays on Samya (Equality), published in the 1870s in Bangadarshan magazine. The People’s Archive of Rural India has preserved these texts. They make for uncomfortable reading if one believes in the BJP’s worldview.

On caste, Bankim Chandra wrote: “Of all the unjust distinctions that humans have created, India’s caste system is the most severe and most abhorrent.”

He went further: “The difference between Brahmin and Shudra is an artificial difference. That Brahmin-killing is a grave sin whilst Shudra-killing is a minor offence—these rules violate natural law.”

Calling the caste system “against natural law” sits rather awkwardly with the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the BJP’s ideological parent, which has historically defended the varna hierarchy.

On property, Bankim Chandra echoed Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Jean-Jacques Rousseau: “Property is not individual but belongs to all. The earth that sustains everyone’s life was not created for any single person. Therefore, all have equal rights to land.”

On women’s rights, he argued that widows should have the same remarriage rights as widowers—radical for 1870s India. He wrote that “education will give women the capacity to earn their livelihood”. These are radically left positions vis-à-vis the stance of Hindutva icon Bal Gangadhar Tilak on such issues.

One struggles to reconcile these views with a party whose economic policies favour corporate interests and whose social policies rarely challenge patriarchal norms.

The cat who talked like a socialist

Bankim Chandra’s satirical essay “The Cat” (Biral), from his collection Kamalakanter Daptar, takes aim at capitalism. A cat argues with the writer about theft. The cat makes an uncomfortable point: “It is because of the rich that the poor become thieves. Why should one person hoard food for 500 people, depriving those 500? If he does not give his surplus to the poor, the poor will steal—no one is born to starve.”

When the protagonist protests, “Stop, stop, cat! You are talking like the socialists!” Bankim Chandra is clearly acknowledging socialist thought.

The Indian government’s own cultural portal notes that Bankim Chandra’s political philosophy drew from “Comtean positivism, Benthamite utilitarianism, John Stuart Mill’s social and gender philosophy, and French socialist currents”.

Why did Bankim Chandra’s exemplar of Bengal’s peasant include “Hashim Sheikh” (a Muslim name) alongside “Rama Kaibartta” (a lower-caste Hindu name)? Because class oppression mattered more to him than religious identity.

Using such a writer for communal mobilisation requires either profound ignorance or deliberate distortion. The BJP appears guilty of both.

The anti-British subtext that everyone missed

The BJP’s central claim about Chattopadhyay’s legendary Anandamath is that it depicts Muslim aggression against Hindus. Academic research suggests otherwise.

Nakul Kundra of Panjab University argues that Bankim Chandra wrote Anandamath “with the covert purpose of rousing people for a retaliatory attack against the British, and the criticism of Muslims was only incidental.” The portrayal of Muslims as antagonists “was a strategy to mislead the British”.

The evidence is compelling. First, Bankim Chandra worked as a Deputy Magistrate for the British government for 33 years. Direct anti-British writing would have ended his career.

He, on the one hand, loved his job like any upper-caste Bengali Bhadralok, but, on the other, he was perturbed by foreign occupation. This duality is manifested in his work.

Chattopadhyay was known for his humour too. When Ramakrishna Paramahamsa asked why his name was “Bankim” (meaning “bent”), he joked: “I got bent from kicks of English boots”—revealing his suppressed resentment.

Second, the historical Sannyasi-Fakir Rebellion (1763-1800), which inspired Anandamath, was a joint Hindu-Muslim uprising against British rule. The Week magazine’s research confirms that both communities participated. Bankim Chandra deliberately omitted the Muslim fakirs from his novel as part of a strategic choice to disguise his real target.

Third, when the serialisation in Bangadarshan included objectionable language against British soldiers, Bankim Chandra was promptly demoted from Assistant Secretary to Under Secretary, with an Englishman taking the higher position.

Chandrika Chakraborty of McMaster University writes in “Reading Anandamath, Understanding Hindutva” that the Sangh Parivar’s goal is “to suppress the ambiguity and contradictions in Bankim’s writings, presenting issues of history and politics as common sense for a ‘national’ community”.

So the BJP’s claim that Anandamath depicts Muslims as ‘the enemy’ is a simplification bordering on falsification.

Vande Mataram’s inconveniently secular history

Historical records contain no evidence that “Vande Mataram” ever incited violence against Muslims. For armed revolutionaries, it was an anti-colonial mantra—not a call for communal war.

After the 1905 Partition of Bengal, “Vande Mataram” became the supreme symbol of Bengali nationalism—Hindu and Muslim alike. The British banned it because it mobilised anti-colonial sentiment. The British didn’t record anywhere Hindus using the song to mobilise against the Muslims of Bengal.

Bengal’s youth icon Khudiram Bose (18) uttered “Vande Mataram” on the gallows. ‘Master-da’ Surya Sen declared a provisional revolutionary government after the Chittagong armoury raid, amid chanting of “Vande Mataram” and “Inquilab Zindabad”. Benoy-Badal-Dinesh used the slogan during their attack on the Writers’ Building.

Notably, in 1906, more than 10,000 Hindus and Muslims marched together in Barisal with “Vande Mataram” banners. Abdul Rasul, a Muslim barrister, sang “Vande Mataram” while presiding over the 1906 Bengal Provincial Conference. Research has found no evidence that Bengali revolutionaries ever used “Vande Mataram” for Hindu-Muslim communal violence.

The BJP now wants to cage the song within Hindutva sentiment alone. But whenever historical light falls upon it, the song reveals itself as a political symbol incompatible with narrow religious identity. This pluralist historical reality is awkward for the BJP—their electoral narrative about “Vande Mataram” collapses under historical scrutiny.

Muslim characters that complicate the narrative

Calling Bankim Chandra anti-Muslim requires ignoring substantial portions of his work. His first Bengali novel, Durgeshnandini (1865), features Ayesha, a Pathan Muslim princess depicted as complex, sympathetic and morally elevated. Ayesha saves the Hindu heroine Tilottama from her own father, sacrifices her own love and helps unite the Hindu lovers.

In Rajsimha, Bankim Chandra wrote: “Whoever possessed religious virtue—be they Hindu or Muslim—was superior”. Placing moral superiority above religious identity—is this the work of a communal writer?

In real life, Bankim Chandra supported Hindu-Muslim peasant unity. As Deputy Magistrate in Jessore during the Indigo Revolt, he consistently ruled for the peasants. He supported the Pabna Peasant Movement, where Hindu and Muslim farmers fought together against Hindu landlords.

So Bankim Chandra’s historical position respected a multi-religious society. His political language never favoured anti-Muslim communalism.

Three political dangers of appropriating Bankim Chandra

The more the BJP claims Bankim Chandra as its symbol, the clearer their contradictory position becomes. The ideological gulf between Bankim Chandra’s literary-philosophical thought and current right-wing politics is so stark that the project itself supplies arguments against the BJP.

The conflict is sharpest in three areas.

First, Bankim Chandra’s class consciousness, anti-exploitation stance and egalitarian thought run completely counter to the BJP’s economic policies. A writer who declared “property belongs to all” and “the rich create poor thieves”—making such a man the symbol of a corporate-friendly, neoliberal party is a self-contradiction.

Second, “Vande Mataram” was never confined to one religious identity. Today’s attempts to communalise it only expose the BJP’s intentions. History testifies it was a slogan of multi-religious revolutionary movements.

Third, Bankim Chandra’s anti-caste, feminist and humanist philosophy directly clashes with RSS social doctrine. Unveiling the writer’s true face reveals he is quite unusable on the Hindutva stage.

Bengal’s resistance and the BJP’s cultural tin ear

The game the BJP is playing is not merely historical distortion but an attack on Bengali cultural identity. Bengali cultural identity has always been expansive, not exclusionary. From Bankim Chandra and Rabindranath Tagore to Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Kazi Nazrul Islam—Bengal venerates its luminaries for their secular intellectualism, not religious ideology.

Even the BJP’s own Bengali leaders understand the strategy’s flaws. During a media interaction a few months ago, MP Abhijit Gangooly said, “Those non-Bengali leaders who cannot understand Bengal’s emotions and pride cannot defeat Mamata Banerjee.” Recent acts—Amit Malviya’s comment that “there is no language called Bengali”, JP Nadda’s error about Tagore’s birthplace, and the breaking of Vidyasagar’s bust in 2019—have irritated Bengali voters.

Exploiting the situation, Chief Minister Mamata Bandopadhyay has weaponised cultural debate, successfully branding the BJP as “anti-Bengali”.

History as foundation, not fabrication

If the BJP believes transforming Bankim Chandra into a Hindutva icon will yield electoral gains, those gains may prove temporary but not durable. Bankim Chandra was a multi-dimensional writer, colonial critic and social reformer. Attempts to bind his work within a one-dimensional communal framework—including the Hindutva project—ultimately produce opposite results.

Bankim Chandra wrote, “all have equal rights to land”. He had a cat declare, “the rich create poor thieves”. He believed “Hinduism cannot exist without universal love”. Making such a man a tool for narrow communal politics insults not only history but Bengali cultural heritage itself.

The authentic reading of Bankim Chandra stands against the BJP. His literature says it clearly—he was militant against exploitation, inequality and colonialism; never for religious division. Bengal’s people know who their cultural heroes are and what they fought for. When someone attempts to make Bankim Chandra a symbol of Hindu polarisation, they actually destroy his true legacy—which was social justice, rationalism and universal humanism.

Therefore, the way the BJP wants to use Bankim Chandra ultimately increases their own political difficulties—because history, literature and Bankim Chandra himself support none of the BJP’s narrative. Standing against this distortion means not merely protecting one writer but protecting Bengal’s pluralist cultural soul.

The irony is delicious. A party that prides itself on cultural nationalism has picked a cultural icon who would have found its entire project rather vulgar. One suspects Bankim Chandra, watching from wherever dead socialists go, is having the last laugh.

Unsigned articles of People's Review are fruit of the collective wisdom of their writers and the editors; these articles provide ultimate insight into politics, economy, society and world affairs. The editorial freedom enjoyed by the unsigned articles are unmatchable. For any assistance, send an email to [email protected]