Afzal Guru continues to test India’s democracy

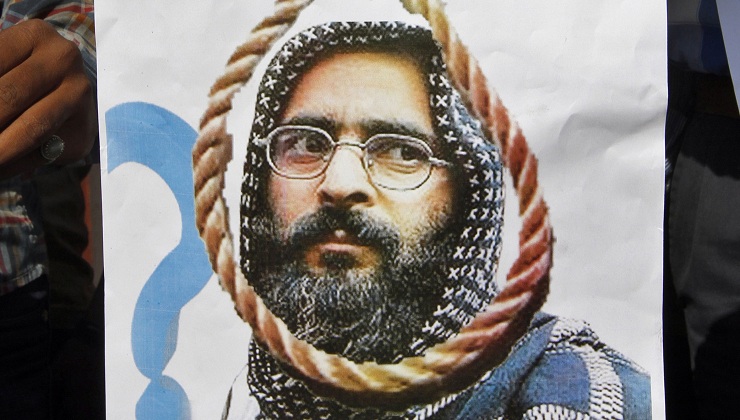

Afzal Guru remains present in death as he never was in life. Three years after the Indian state hanged Guru in Tihar Jail, his case still provokes fierce debate. The 2001 Parliament attack case that led to Guru’s execution raises uncomfortable questions about India’s courts, security forces, and commitment to fair trials. With Narendra Modi’s Hindutva-incensed government in power, the question has become more pronounced than ever.

Conviction built on doubt

Guru came from Baramulla in Kashmir. Police implicated him in the Parliament attack without, critics argue, credible evidence. The alleged perpetrators remained at large, but Guru, like many Kashmiris, became the easiest target. His confession came after torture, his family alleged. An infamous television interview followed, obtained under duress, critics allege. Legal scholars question the trial’s foundation. Yet the courts upheld the conviction and sentence. Guru was hanged in February 2013.

The case illuminates a wider problem. The Parliament attack investigation relied on shortcuts. When investigators faced dead ends, they turned to familiar tactics. Blame those unlikely to mount an effective defence. Target those from troubled regions. Blame Kashmiri separatists. Guru fit the profile perfectly.

His supporters argue that the state committed judicial murder. Guru’s case became emblematic of something deeper: how security concerns can corrode the rule of law in democracies. The actual Parliament attackers have never faced conviction with comparable certainty.

Cartoons and censorship

Mir Suhail Qadri, a cartoonist, drew a simple image. Roots from Guru’s grave intertwined with Kashmir’s struggle. Rising Kashmir published the cartoon. Facebook deleted it. Users complained. The deletion sparked fresh controversy about free expression in India.

Qadri told the Hindustan Times that the incident revealed “how fragile the freedom of expression is in India.” He reposted the cartoon. Facebook removed it again. The pattern repeated. A cartoonist’s attempt to comment on injustice became itself an instance of censorship.

Campus reckoning

At Jawaharlal Nehru University in February 2016, students planned a cultural programme about Guru’s case. The event aimed to examine whether India’s courts had dispensed justice or merely theatre. The university’s vice-chancellor approved the gathering.

The Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), the student wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), intervened. Campus tensions escalated over the programme. ABVP members organised counter-protests. Violence threatened. The vice-chancellor, M Jagdeesh Kumar, revoked permission for the student event.

Saurabh Sharma, the sole ABVP representative in the student union, led the campaign. Other students from privileged backgrounds joined him. They framed the discussion on Guru as “anti-national”. They demanded action against ten students who organised the programme. University authorities have prepared to comply.

The episode mirrored events at the University of Hyderabad the month before, where protests had led to the suicide of Rohith Vemula, a Dalit research scholar. Sharma’s tactics echoed those precedents. By invoking nationalism, his faction shut down debate. Official pressure followed. The left-wing students became the easy targets—just like Guru was, for the establishment.

Hypocrisies that persist

Political contradictions mark this history. Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and RSS backed Guru’s execution fiercely. Both championed his hanging as necessary for national security. Yet both later allied with Kashmir’s People’s Democratic Party, which had opposed Guru’s execution. That party governs Jammu and Kashmir in coalition with the BJP. Their “nationalism” proved flexible when power beckoned.

Such inconsistencies suggest that support for Guru’s execution followed factional lines rather than principled conviction. The execution served a purpose: it appeased the “collective conscience of the majority”, as the apex court had said. It silenced awkward questions about security and justice.

What remains unresolved

Eight years on, Guru casts a shadow. His case remains contested. Lawyers continue to question the trial’s legality. Journalists probe the investigation’s gaps. Students argue about its implications for democracy. The state hanged a man when guilt appeared uncertain. It did so in haste. It did so, supporters say, to make a point.

The Parliament attackers themselves never received comparable attention from courts. Some remain unaccounted for. Others may have evaded serious prosecution. Guru, by contrast, faced certain death.

In this inversion lies the case’s enduring significance. It reveals how democracies can use courts to project strength while actual accountability remains elusive. Guru’s execution satisfied demands for vengeance. It resolved nothing about whether the courts had found the true culprits. Perhaps they had. Perhaps they had not. The trial left ambiguity. It left doubt. And in a functioning democracy, doubt should trouble the conscience.

Unsigned articles of People's Review are fruit of the collective wisdom of their writers and the editors; these articles provide ultimate insight into politics, economy, society and world affairs. The editorial freedom enjoyed by the unsigned articles are unmatchable. For any assistance, send an email to [email protected]