Bangladesh: Mob rule burns democracy

Dhaka in December is a peculiar city. By day, people commute to work. By evening, they return home. Normality, it would seem. But scratch the surface—or simply scroll through social media—and the abnormality reveals itself. Bangladesh is experiencing a surge in mob violence and Islamist militancy.

It’s unfolding before the world’s eyes.

Online, armchair strategists plot war against India.

Critics of the new order are branded “fascists” with remarkable speed.

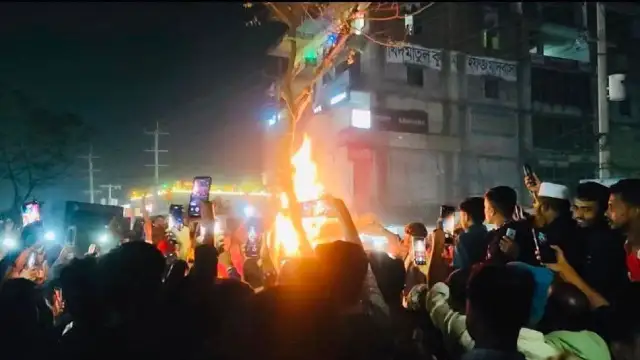

Meanwhile, Dhaka burns. Mymensingh burns.

Yet ordinary citizens’ blood and spirit remain curiously unignited.

Bloody December: One murder, many consequences

On December 12th, motorcycle-borne gunmen shot Sharif Osman Hadi, convener of Inqilab Mancha, a hardline Islamist organisation, on a Dhaka street. Six days later, he died in a Singapore hospital. The reaction was unprecedented in Bangladesh’s recent history.

A two-day nationwide strike followed. Protests erupted. But when demonstrations turned violent, the targets were telling.

No, none of the government departments responsible for the security lapse that allowed assassins to target Hadi, a promoter of mob violence himself, faced the wrath.

The mob targeted newspaper offices, cultural centres and innocent bystanders. Arsonists torched the offices of Prothom Alo and the Daily Star. Dhaka’s streets witnessed destruction.

Two West-based social media influencers have been accused by one of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party’s (BNP) national leaders of provoking the mob.

The worst, however, occurred in Bhulakipur, Mymensingh.

Dipu Chandra Das. Twenty-three years old. A garment worker. A Hindu. That was his only “crime”. A mob lynched him on a fabricated blasphemy charge. They then hanged his corpse from a tree and set it ablaze—a message, evidently. The message was clear— in Bangladesh, some lives are considered worthless by the mob.

The blasphemy allegation against Das appears to have been a convenient fiction. Reports suggest his actual dispute with factory management concerned production targets and wages. The owners of Pioneer Knitwear allegedly fabricated the claim that Das had insulted the Prophet Muhammad.

Twelve arrests have followed. Yet the interim government, so keen to cultivate Western approval, has done nothing to address the grim reality that any minority citizen can be handed to a murderous mob on a false accusation—and that killers can proudly circulate videos of their handiwork on social media.

Bangladesh’s sees Islamic militancy’s alarming return:

A recent report from Singapore’s S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) makes for disturbing reading. Since the government changed hands in August 2024, more than a thousand prisoners have escaped Bangladesh’s jails. At least 70 armed militants were identified among them.

The jailbreaks are not the half of it. Some 5,800 weapons and hundreds of thousands of rounds of ammunition were looted during the chaos. Where are these arms now? Whose hands hold them? Nobody knows. Or if they know, they are not saying.

More troubling still, over 300 terrorism suspects have been granted bail. Among them are members of Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh and Ansarullah Bangla Team. Mufti Jasimuddin Rahmani, accused of leading ABT, now claims his organisation never existed. A remarkable denial.

These militants in Bangladesh have helped incite mob violence, at the grassroots, it’s alleged.

Flags, symbols that streets reveal

What Dhaka’s protests have displayed over the past 18 months is not ordinary political dissent. Black flags of the Islamic State and al-Qaeda have flown. Portraits of Osama bin Laden have been paraded. Anyone who dismisses these as “isolated incidents” is either blind or deliberately closing their eyes.

The RSIS report notes that Pakistan-based terrorists are actively recruiting Bangladeshi youth. These young men are mostly from rural areas, who suffer discrimination in the cities, where the elites look down on them.

Online propaganda flows freely. Youths in Bangladesh are encouraged to participate in mob violence. Young minds are being poisoned—assisted by Islamist militant networks that have grown stronger with Turkish government backing. The interim government watches. And watches. And does nothing.

From Hefazat to politics

The most alarming development is that Hefazat-e-Islam and other extremist outfits now seek electoral participation. They are pursuing political alliances. The 2026 election is their goal. Sheikh Hasina once built and nurtured Hefazat. The Islamist forces that grew under her government’s patronage now seek to erase whatever democratic residue remains in Bangladesh’s political landscape.

This is not merely a political calculation. It poses a fundamental question about Bangladesh’s future. What happens when those who consider democracy “un-Islamic” participate in democratic processes? The answer is simple—they will use democracy to destroy democracy. Bangladesh can see a glimpse of it as mob violence engulfs the nation.

Women’s rights activists, religious minorities and secular intellectuals are already worried. Their concerns are not unfounded. In a country where a young worker can be lynched for his faith, nobody is safe.

Government response: Much talk, little action

The interim government has issued statements. Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus has spoken of “certain extremist groups” causing disorder. He has appealed for peace. The government has promised justice.

But promises and reality remain distant cousins. How many of Das’s killers have been arrested? Have those who attacked newspaper offices faced punishment? Has the indiscriminate bailing of terrorism suspects stopped?

The Bangladesh Hindu-Buddhist-Christian Unity Council has condemned Das’s killing as “barbaric” and demanded the harshest punishment. But demanding and delivering are different things. In this country, demands come cheap. Justice does not.

International reaction: Bangladesh through foreign eyes

India is furious. New Delhi summoned Bangladesh’s ambassador. It protested the demonstrations outside its mission. Diplomatic relations between the two countries are strained.

But a question lingers. When India protests, is it genuinely concerned about religious minorities’ safety, or is it pursuing its own political interests? The answer is complicated. One thing, however, is clear— Bangladesh’s internal problems have become international news. This is a matter for shame, not concealment. The neo-Islamist nationalism now ascendant in Bangladesh—which labels everything “fascism”—is handing India weapons to use against its own country.

Attacking journalism, burning truth

The attacks on Prothom Alo and the Daily Star were not merely assaults on two newspapers. They were attacks on truth itself. Those who burn newspapers want to burn information. They want people to remain in darkness. They do this in the name of defeating “fascism”. Yet they cannot tolerate criticism of themselves. Those who accused Hasina of silencing voices now seek to silence others.

When a journalist is threatened, thousands of readers are denied the truth. When a newspaper office burns, a pillar of democracy collapses. Understanding this requires no doctorate in political science. When university-educated youth support such actions, it becomes clear they are knowingly endorsing neo-fascism.

Looking ahead: Bangladesh and mob violence

Ain o Salish Kendra, the human rights organisation, has warned that unless this violence is checked, it will create a permanent crisis for human rights and democracy. The words are harsh but true.

Bangladesh faces several urgent tasks. First, the indiscriminate bailing of terrorism suspects must stop. Second, looted weapons must be recovered. Third, minorities must be protected—not on paper but in reality. Fourth, journalists and cultural workers must be safeguarded.

Above all, political parties must decide: will they ally with extremists, or will they save democracy? The two are incompatible.

It was precisely the dominance of these extremist Islamist forces after the 2024 monsoon uprising that prompted the BNP and the left to intensify their efforts to protect the constitution and democratic system.

Though Jamaat-e-Islami once rode on BNP’s shoulders to establish itself in independent Bangladesh’s politics, after 2024, it has conveniently cast BNP aside.

Final question: Will Bangladesh survive?

Bangladesh’s existence depends on how it battles two forces.

On one side stands the Awami League and its allies, backed by India, seeking to reduce the country to a New Delhi colony. On the other side stand Islamist militants, willing to sell the nation’s independence to Western powers while creating a puppet government modelled on Ahmad al-Sharaa’s Hayat Tahrir al-Sham in Syria—weakening Bangladesh from within.

The current faces and masks of these two forces may one day fade from history. People may forget who they were. But that day will come only when a new Bangladesh, built by people of all faiths and ethnicities, defeats them both.

As long as youth are seduced by militant ideology, as long as minorities live in fear, as long as journalists face threats—these two forces will survive. The question is: will Bangladesh accept this reality, or change it?

The answer lies in our hands. Time is running out.

Editorial desk of People's Review provides you the editorial view point and also shares the outlook of the collective wisdom that manages the publication. Send letters to the editor at: [email protected]