Death under scrutiny: Ujjain woman Ayati Vashist dies mysteriously in Britain

A telephone call from London reached the Pandey household in Ujjain on July 3rd, 2016. Nikhilesh Prasad Vashist, the father-in-law, informed them that their daughter Ayati Vashist had died. He described her death as suicide by hanging in a bathroom. The family received little detail beyond this initial report.

The news struck like a sudden fracture in the family’s world. Ayati, previously known as Sonu Pandey, had left her job at the Madhya Pradesh government three years earlier. She had married Akanksh Vashist, a mathematician employed by a reputed UK bank, in April 2013. The couple had recently returned to London from the Ujjain Kumbh festival. The call offered few answers about what had prompted such an act.

Questions that follow Ayati Vashist’s death

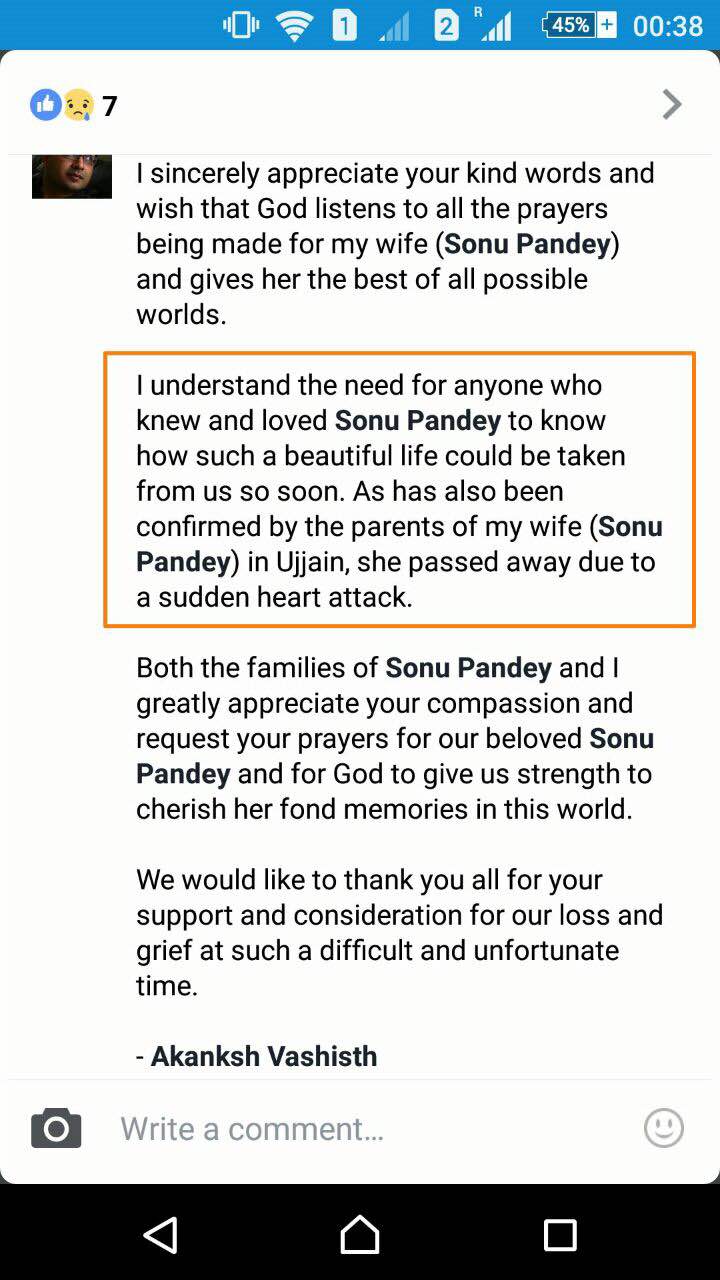

Inconsistencies emerged quickly. Akanksh Vashist posted on Facebook that his wife had died of a sudden heart attack. Yet his father had claimed suicide by hanging. These conflicting accounts troubled the Pandey family deeply. They initiated contact with Ilford Police on July 2nd. The authorities assigned case number CAD 8879 to the matter.

The family expected a swift investigation. Repeated emails to the Metropolitan Police and Ilford station brought silence. No officer provided updates on the case’s progress. The post-mortem report remained unavailable. The Vashist family refused to share details with Ayati’s relatives in India. This reluctance intensified the family’s doubts about the suicide narrative.

Sanjay Pandey, Ayati’s brother, pressed authorities for answers. He tweeted appeals to External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj. The Indian Embassy in London proved similarly unresponsive. Neither the police nor the embassy provided copies of the post-mortem report or investigation findings. A month passed with no public updates from police or news coverage of the case.

Control and isolation: Ayati Vashist’s life in the UK

The couple had met through Shaadi.com, a matrimonial website. After arriving in Britain, Ayati found herself confined largely to her husband’s home in Ilford. Contact with her family became restricted. The Vashist family seldom reached out to relatives in Ujjain except on formal occasions. This isolation proved significant to her family’s later concerns.

Within months of the marriage, relatives discovered Akanksh had been married before. Ayati learned of the previous marriage only upon reaching the UK. This revelation prompted increased pressure from her in-laws. Demands for additional wealth accompanied stricter household control. The family alleges that the Vashist family extracted approximately 200,000 rupees in cash and jewellery during the marriage. Other gifts in kind supplemented these payments.

Repeated pleas from Ujjain for relief went unanswered. Ayati’s family members expressed concern about the continuous pressure. Yet the situation never eased during the three years of marriage. Friends and family members later described Ayati as a strong, determined woman. They expressed disbelief that she would take her own life.

Dowry deaths across borders

Indian law criminalises dowry demands and recognises dowry-related deaths as serious offences. When married women die within years of marriage, suspicion automatically falls on the husband and in-laws. Such legal protections emerged from decades of activism against dowry murders. India’s lawmakers constructed these safeguards to shield vulnerable women.

Britain lacks comparable legal frameworks addressing dowry practices or related honour crimes. The Metropolitan Police operates without specific guidance on investigating deaths within immigrant families from South Asia. This legal vacuum creates consequences. Women fleeing patriarchal oppression in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh often see Britain as a sanctuary. Instead, the absence of protections can enable the very abuses they fled.

Dowry killings receive limited coverage in the British media. Local police rarely investigate such deaths with the same rigour applied in Indian cases. The Ilford station’s inaction reflected this broader institutional gap. No investigation advanced. No charges were pursued. The case appeared to have closed without proper examination.

Family left without Answers

The Pandey family faced an unusual predicament. They possessed no legal standing in British courts. They could not compel a police investigation from India. They could not access official records about Ayati Vashist. Meanwhile, the Vashist family maintained silence. No public statement clarified the conflicting accounts of heart attack versus suicide.

One month after Ayati Vashist’s death, the case remained officially closed. Police had filed no charges. No investigation appeared to be proceeding. The discrepancies between the father’s and son’s accounts of events—one claiming suicide, the other a heart attack—would ordinarily invite scrutiny. In India, such contradictions would trigger a fresh inquiry. In London, they prompted no action.

The case of Ayati Vashist illustrates a troubling gap in international protections for women. Families within Britain from South Asian backgrounds live under legal regimes designed for different social contexts. British law addresses murder and abuse directly, but lacks mechanisms to recognise dowry coercion specifically. This absence can render vulnerable women nearly invisible.

As the Pandey family searched for justice across continents, Ayati Vashist’s death remained officially unexplained. Whether ruled a suicide or heart attack, the questions surrounding her life in London persisted. The inconsistent accounts went unchallenged. The pressure she endured remained undocumented. And in the absence of a determined investigation, the full circumstances of Ayati Vashist’s death may never be known.

An avid reader and a merciless political analyst. When not writing then either reading something, debating something or sipping espresso with a dash of cream. Street photographer. Tweets as @la_muckraker